“Hollywood doesn’t move at the speed of culture.”

That’s how Max Reisinger—founder of Creator Camp and one of the most exciting young voices in this creator-led movement—summed up the moment we’re in. And he’s right.

There will always be demand for Oppenheimer or Barbie, always shows like Stranger Things or Wednesday that need time, scale, and institutional muscle to exist.

Hollywood, in the right circumstances, can still make culture—but it’s become rarer and more difficult to accomplish. Most of the culture now moves at the speed of Wi-Fi, and it’s coming from the creator engine, not the studio lot.

The next seismic disruption is coming—the niche comedies, indie dramas, low-budget horror films. That’s where creators are going to hit hard. And soon. (And by soon, I mean it’s already starting to happen).

The Creator Economy’s Founding Logic: Launch First, Figure It Out Later

As I start building new models that merge our legacy film and television expertise with the creator space, I’ve had to shed a lot of old instincts. One conversation in particular—like most good lessons—came wrapped in a burn. It was with a friend, someone who’s spent her career as a strategist and brand whisperer, and now lives deep inside the creator economy.

I told her we’d found a compelling white space, a frontier between traditional storytelling and creator-driven content, and that I wanted to raise capital to jumpstart it.

She laughed: “You are so Hollywood.”

It stung. But I pressed on.

She explained: “That’s not how creators do it. They start with an idea. They make it. They hope it brings an audience. And if it works, that audience becomes a community. And then they build from there.”

In other words, they don’t start with infrastructure. They start with intuition.

Case Study: Creator Camp and the Power of Scrappy

That logic came to life as I read about Creator Camp —a two-day creator-first film festival launched in Austin by Max Reisinger, Simon Kim, and Chris Duncan on a $200,000 budget and a ton of belief.

No venture capital. No studio partnership. They self-funded, crowdsourced, built trust online—and just launched. Held at the Paramount Theatre, the inaugural event sold over 1,100 tickets, premiered 10 films (created in just three months), and offered something more authentic than anything I’ve seen from traditional media in years.

Their origin story?

A few years ago, fed up with over-produced social media content, they retreated into the Montana woods to reimagine storytelling. From that moment came the #YouTubeNewWave—a philosophy of raw, honest filmmaking that connects with audiences in real time. They’ve since hosted gatherings around the world and, in fall 2024, launched Camp Studios to turn that philosophy into a tangible platform for creator-led cinema.

Since that retreat, Creator Camp has evolved into a full-fledged ecosystem. They’ve organized retreats and events in Colorado, Utah, New York, France, and Switzerland—spaces for unplugging, collaborating, and reconnecting with the essence of storytelling.

They've partnered with brands like Coca-Cola and Spotify, worked with tourism boards to support projects, and used platforms like Discord to build community. At its core, the initiative is about bypassing legacy gatekeepers and designing a new economic model for indie film—one powered by connection, not convention.

What sets them apart, though, isn’t just the scrappy execution—it’s the intention to nurture real craft. Creator Camp’s mission is as much about education as it is disruption: teaching storytelling fundamentals, instilling care, and elevating creative standards. This isn’t just about giving creators access. It’s about helping them level up. As Max told Colin and Samir, “If we’re going to build something lasting, we have to care about the work. Not just the view count—but the craftsmanship.”

And crucially, they believe theatrical still matters.

Theatrical Math—And Why It Might Just Work

In his interview with Colin and Samir, Max made the case that if a director could earn even $250K in profit from a theatrical release of a $100K film, that would already qualify as a big win. Let’s run the numbers.

Say the movie costs $100K to make. Add another $100K to prep it for theaters—everything from a Dolby Atmos sound mix to a DCP, a lean but serious marketing push, and maybe a team to run targeted digital. Add another $300K in.

If your rentals are 50%, to break even, you’d need to make $1 million at the box office. With an average $10 ticket, that’s 100,000 tickets sold.

Now let’s double it:

200,000 tickets.

That’s $2,000,000. That’s $500K back.

Half to the filmmaker? Seems fair. And Bob’s your uncle.

Here’s the more interesting question: if you can theoretically get millions of views on YouTube, could you convert even 5% into moviegoers? For the right movie, seems more than reasonable. That’s a model with leverage—and it makes a lot more sense than the current system. Especially if you are making these small movies at scale. Roger Corman for the Art House.

Slacker—one of the defining indie hits of the ’90s—made around $1.2 million at the box office. Adjusted for inflation: $2.86 million. At the time, it was tiny—and still a huge win. It launched Richard Linklater’s career.

And like this there are a million examples. An audience that wanted their own cinema. A filmmaker who spoke to them. A method of distribution that reached them.

The Legacy Lesson: Don’t Retrofit—Relearn

For those of us raised inside the walls of legacy media, this is deeply uncomfortable. The open garden doesn’t follow our rules. Creators don’t wait for permission. They don’t plan every beat. They plant seeds and see what grows.

That doesn’t mean our knowledge is useless. It means it needs translation.

The opportunity for companies like mine isn’t to chase the next viral moment or bolt ourselves onto creator culture. It’s to listen, learn, and build with—not over—this next wave.

We've Been Here Before—Sort Of

Disruption isn’t new. The French New Wave disrupted stodgy European cinema. The ‘70s auteur movement broke open the studio system. The ‘90s gave us Quentin Tarantino, Kevin Smith, and Robert Rodriguez (who basically invented creator filmmaking long before we called it that).

There was even a lesser-known but wildly prescient moment in the early 2000s when Ira Deutchman launched Emerging Pictures, connecting digital projectors across museums and universities to create an outsider theatrical network. It was one of the earliest attempts to reimagine theatrical distribution for a decentralized, digital-first age—quietly radical, and possibly a blueprint for what’s coming next.

Or think of Jason Blum, who could barely get Paranormal Activity distributed—no one thought a movie this cheap (less than the Creator Camp movie actually) could work. So he marketed it by showing audiences screaming in night-vision trailers. He let fans request screenings in their towns. He read the culture before it had a name.

What’s different now is scale. Tools are cheaper. Distribution is instant. And the audience is already assembled—just waiting for something that speaks to them.

The Creators Are Coming from the Bottom Up

Here’s the disruption, plain and simple: creators aren’t trying to make Oppenheimer. Right now, they’re trying to make the kinds of smaller indie films that Hollywood has largely abandoned—the comedies, dramas, and low-budget genre pieces that once filled the margins of the moviegoing experience.

And if they can do it at a fraction of the cost, market it with fluency legacy can’t replicate, and draw real people into communal experiences again—well, that’s not just a niche. That’s a wedge.

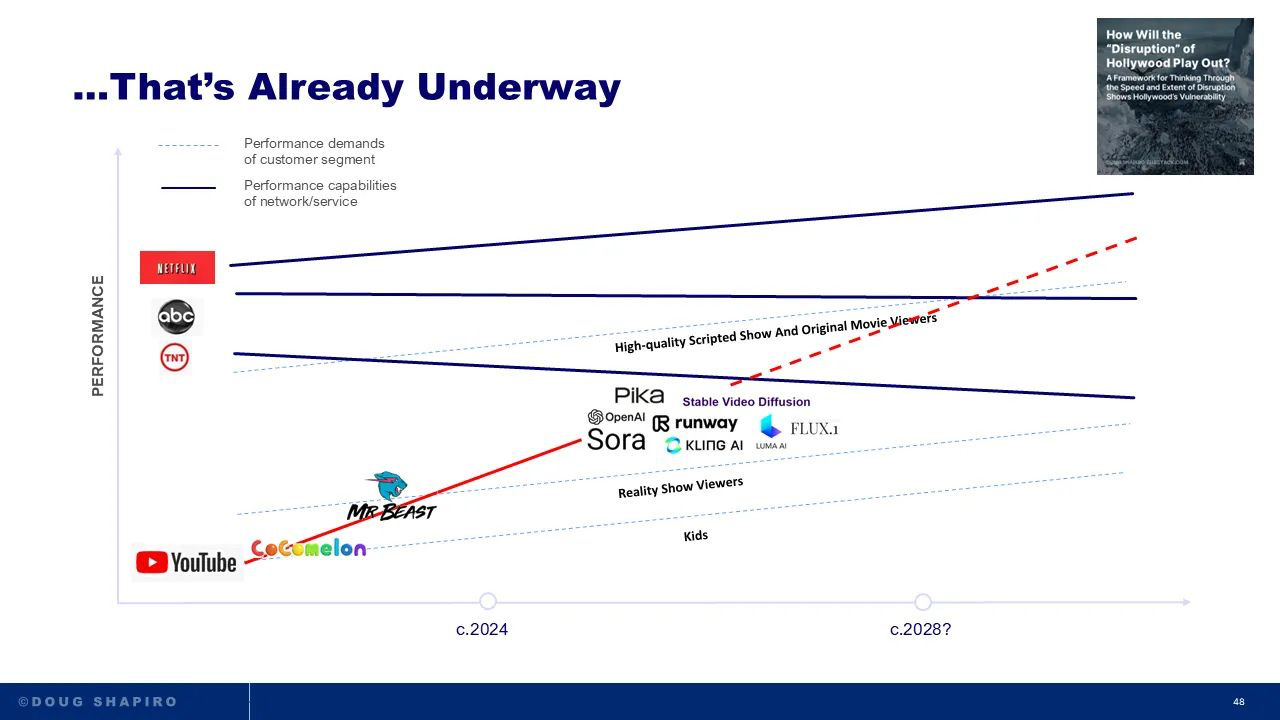

Think about Doug Shapiro’s graph of disruption. It always starts with the edge—then moves inward.

Now apply it to movies. First the micro-budget indies. Then the mid-budget. Eventually, even blockbusters get redefined.

Where Legacy Media Leans In

So how does legacy media play in this sandbox?

For one, there’s now a new recruiting ground for emerging filmmakers. And because the costs are so low, there are artists entering the space who never could have played in the “under $5 million” indie model which is still a walled garden hard to access. This is opening the door wider than it’s ever been.

Now, when a filmmaker goes from making a $100K film to a $20 million one—if that’s the direction they want to go—they’ll need infrastructure. They’ll need the experience and systems that legacy producers and studios bring. (That’s assuming they don’t choose to just keep making films this new way using the proceeds to create more like they do on YouTube.)

Secondly, clever producers can build incubators using the same blueprint. Jason Blum could do this with horror. Chad Stahelski could do it with action. Hello Sunshine could do it with female-forward storytelling.

The model is flexible—the challenge is scale.

Think about Blum again. He already makes 8–10 films a year, not all of which go theatrical. But what if he made 24 or 48 or 96? And a dozen went theatrical? And two became the next Paranormal Activity?

It’s not unprecedented. AwesomenessTV and others have tried versions of this. But the culture wasn’t ready then in the way it seems to be now. The appetite has shifted toward something looser, more direct, and more community-powered.

The question is: would the audiences who support this movement still support it if it were propped up by Hollywood?

The End—or Just the Beginning?

We don’t know if this is a movement yet—but the signs are good.

And the more I dig, the more I believe we’re not heading toward one singular disruption, but many. We live in a world of narrative whiplash, where every new headline announces the next model that will change everything. But the truth is, the disruption is happening everywhere, all at once. And there won’t be one model that wins.

Creator Camp has shown us one possible new path. And there will be many.

But listening to Max on the Colin and Samir podcast reminded me of the excitement of making movies right out of film school. The first one I made cost $200K and we had a crew of fifteen.

The second, we shot in New York, Mexico, and California—mostly without permits (though we were SAG), stealing shots on subways, in Chinatown, or with a five-person crew on the border, where we literally ran for our lives when the contrabandistas got antsy.

We won the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance. Then we struggled to get distribution. We couldn’t break even. I didn’t even take a producer fee.

And yet—it was so fun. So anti-establishment. So exhilarating. They were some of my favorite experiences “in the business.” Even though we thought we were rebels, we were still playing in the same sandbox as everyone else—and it was so restrictive.

These guys are playing with that same young, reckless spirit. And maybe, just maybe, they’re building their own sandbox. If they stay focused on quality and craft, and give it everything they’ve got, that momentum will take them places. And it might just remind some of us legacy folks why we got into this in the first place.

I’ve been postulating for some time that the next Sean Baker—the writer/director of Anora—is going to emerge from the creator space. Someone making handcrafted short films, finding their audience not through distributors or festivals, but by putting honest art into the world on YouTube and Patreon and letting the world find it.

And maybe it won’t just be films. Imagine what a Sean Baker could do with a podcast—something like Shittown, that starts as true crime and transforms into a gut-punch meditation on art and humanity. Or pop-up plays that tour the country. Or merch that doesn’t feel like merch, but like emotional residue. A music label curated by our filmmaker, who directs the music videos and weaves them into his soundtracks—which leads to live shows and touring.

It’ll be a universe. Of art. Of story. Of direct connection. And if they build that community—and monetize it in smart, authentic ways—it becomes an ecosystem. One that sustains the artist. One our indie predecessors never had.

Patreon has been paving the way. Creator Camp is part of that movement.

A flywheel that feeds the audience. So the artist doesn’t need a big audience—just a loyal one that will keep that wheel spinning.

Many of us thought the dslr would launch a French New Wave style revolutionary cinema movement in the early 2010s, and it definitely birthed a generation of filmmakers, but we needed the distribution technology to mature, and the culture to be ready.

There’s so much talk about the death of Hollywood. And this gets incorrectly conflated with being the death of cinema — which is far from true.

Yes. I think a certain segment of Hollywood is dead. But for ALL the reasons you so eloquently address here, and many more, I personally believe some of cinema’s most exciting times are right around the corner — which means they are really happening now. THIS is the revolution we thought would happen long ago.

“The dream of the 90s is alive in Portland”, and in film culture.

Amazing ideas here. Keep it up and let me know how I can help. Same mentality that led to Slamdance.