Community is the single biggest thing legacy media still does not understand.

Not how to market it. Not how to label it. How to actually build it. How to maintain it. And why it matters more than any distribution strategy now on the table.

I had spent the last few years thinking about community through decks, case studies, creator economy conversations and the way my production companies is producing our content.

But I understood it more clearly after my house burned down.

Open Gardens is about exploring the convergence of legacy media and the creator economy. But to start this year, I want to step back and reflect on 2025 through an experience that fundamentally sharpened how I think about community, not as a buzzword, but as infrastructure. Next week we will jump back into more practical case studies and observations. Today— Im going personal.

On January 6th, 2025, just a year and one week ago, my house and my community burned down in the Palisades fires. For me, and for many others, the Palisades and Eaton fires altered our lives so quickly and so completely that it is impossible any of us have fully processed what happened or how our lives have changed and will continue to change.

But the decision my wife and I made in the days that followed reshaped how I now understand community more than anything I have read from a social media pundit or any case study about Taylor Swift.

We decided to move to her hometown of Manizales, Colombia. I knew I would live on airplanes and occasionally in the pool house of close friends in LA to keep work moving. Still, after so much trauma, retreating to family felt necessary. My kids speak Spanish and know the city well from Christmases and summers there. This felt like a chance to give them a deeper, more rooted experience of a place that already mattered.

I did not know it would alter my thinking so profoundly.

I grew up with a Colombian family in the US and moved to Bogotá in my 20s, where I got my start as a journalist and eventually as a screenwriter in the 1990s. That is a story for another time. I met my wife years later in Miami and first came to Manizales 17 years ago, when I met her family.

Manizales, high in the Andes, shaped by coffee and mountains.

Manizales sits high in Colombia’s central Andes, in the heart of the coffee region. It was founded in 1849 by Antioquian settlers pushing south, part of a broader migration that shaped much of western Colombia. Coffee built the city. Risk did too. Fires, earthquakes, and the constant presence of the Nevado del Ruiz volcano forced Manizales to rebuild itself more than once. What emerged was a place defined by resilience, education, and civic life.

Today, Manizales has roughly 460,000 residents across the city and surrounding metro area. It remains a mid-sized city with outsized influence, known for its universities, cultural life, and role in Colombia’s coffee economy.

Colombia is one of the most singular countries in the world. Gabriel García Márquez did not invent magical realism. He observed it. Here, it is simply reality. The country is born of passion, of what they call 'berraquera’ (what in Yiddish would be called chutzpah). It is shaped by violence and tragedy, yet somehow that history has produced warmth, a hunger for life, and a sharp sense of humor.

But Manizales is not the hard-edged, metropolitan Bogotá that shaped my 20s. Manizales is something else. It was recently voted the best city to live in in Latin America by the United Nations for quality of life. I have traveled all over Colombia. Manizales operates on a different frequency. I never understood why until I lived here.

It comes down to community. And that community is deeply wired through an equally deep relationship with the Catholic Church.

Let’s pause here. If you are like me, that thought probably short-circuited your brain a little. Organized religion. Worse, the Catholic Church, with all of its very real transgressions. I am agnostic at best. On bad days, I drift fully into existentialism.

But religion here functions differently. And this is not about Colombia as a whole. It is about how Manizales has been built. The city had the capital from its coffee trade to form a strong middle class and, with seven universities, became a center for education and independent thought. It is also physically isolated. The closest international airport is in Pereira, an hour and a half away through winding mountain roads.

And then there is Catholicism.

Colombia has always wrestled with its religious identity. The country has long been shaped by a tension between conservatism and liberalism, with the Church at the center. Conservatives pushed for church and state to function together as the moral backbone of society, while liberals argued for secular government and civil liberties. That divide fueled civil wars, ‘La Violencia’, and decades of instability. The 1991 Constitution formally separated church and state, but the legacy remains. Colombia is legally liberal, culturally conservative in many regions, with faith still acting as social glue.

And Manizales, conservative to its core, is held together by that glue.

None of this should be surprising. We have always understood the power of religious communities to hold people together. They have done it for centuries. I had simply never witnessed it up close. Living in liberal cities, the religious underpinnings that once structured communal life had long since been replaced. In many cases, including my own, our belief systems were forged in explicit rejection of those structures. Faith became something private, or suspect, or irrelevant. What I had not fully appreciated was what disappears when those shared frameworks disappear with it.

It was my idea to move back to Manizales. My wife is the rock of our family. It did not take much logic to see that if the rock had been destabilized, the path forward was to stabilize it.

But when I suggested it, she pushed back. You won’t be happy there. She knows me. She knows a small, conservative city creates friction for me. She said she would not agree unless her brother was on board. So we called him. This was four days after the fire. A Thursday night. I remember it clearly.

“Hermano,” he said. “We are sitting here right now as a family planning for this. We already have a house for you. It will be furnished before you arrive. We have spoken to the international school and your kids have a spot waiting. You just need to tell me what time to pick you up at the airport.”

It was the first time I cried since the fire. I had been in producer mode, solving problems. There was no time to feel anything. That level of humanity and readiness broke through everything.

It was also the beginning of understanding what real community actually looks like.

We moved into a house provided by family. It was already furnished with everything from frying pans to silverware to sofas and beds to televisions mounted on the wall. All new. All gifted.

That was family helping. But then came the larger community.

Neighbors showed up with fruit from nearby farms. The car we bought at a steep discount turned out to be owned by friends of my brother-in-law. The dealership owner later called him to say thank you for allowing them to help.

The more I observed the people close to me, the more I understood how this place works. Mass was only the visible layer. Beneath it were retreats, marriage seminars, and constant, quiet support for people who needed help. No visibility. No credit.

If God is the Creator with a capital C, God is also the center of the community.

The local priest oversees a parish of tens of thousands, while constantly raising money for clothing, food, and emergency aid throughout the city. Not seasonal charity. Ongoing work. And then there are people like my brother-in-law and his wife, operating as connective tissue. Organizing family and friends. Carrying the same values forward without visibility or applause.

Manizales holds together because it is built around shared values. And yes, it excludes others.

That exclusion is not loud or punitive. Nearby cities have been hollowed out by narco-culture and crime. Manizales resists that. Outsiders can come, but on the city’s terms. You do not have to be religious, but you do have to respect the principles.

As a producer trying to understand community, I had always approached it transactionally. How do I get someone to watch a movie or a show. How do I turn attention into loyalty, and loyalty into something that scales. Community, in that framing, is something you build in service of an outcome.

What confused me in Manizales was that none of this logic applied.

What I was watching had nothing to do with conversion, incentives, or visibility. People gave without signaling. Help arrived before it was requested. There was no scoreboard, no recognition, no branding of generosity. And yet the system worked. Better than anything I had seen professionally.

Slowly, I realized the missing ingredient was emotional value. Belonging itself was the asset.

At its core, this community runs on genuine give and take, but not in any linear or traceable way. You contribute without knowing how or when it comes back. Or if it comes back at all. That leap is faith. Not faith in doctrine, but faith in people.

As someone wired more scientifically than spiritually, that was the unlock. This was not sentimental. It was belief in human wiring. That people thrive in communities. That investing in the whole eventually supports the individual.

That curiosity led me backward through the earliest digital communities in the creator economy, long before platforms and playbooks. And that path led me to David Spinks.

Spinks is one of the first people to treat community as infrastructure rather than marketing. He founded CMX, helped professionalize community building, and wrote The Business of Belonging, which became a field guide for understanding why some communities endure and others collapse.

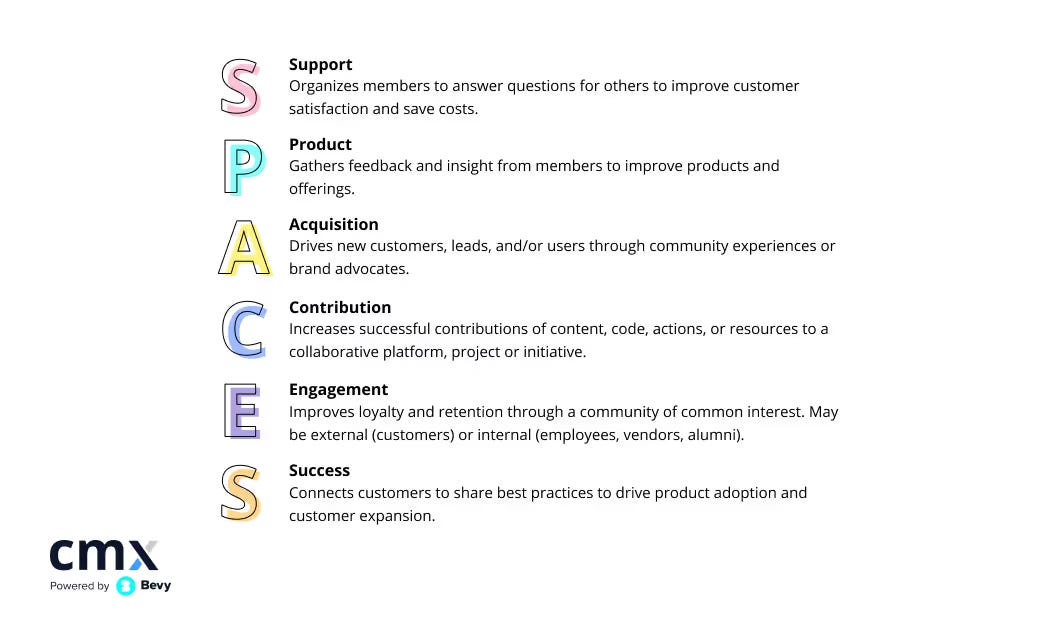

At the center of his work is the SPACES model, which defines six kinds of value communities create. Support, Product, Acquisition, Contribution, Engagement, and Success.

Reading it after living in Manizales was jarring. Because it all mapped perfectly.

Support as infrastructure. Contribution without applause. Engagement enforced socially. Success defined by collective health. Exclusion as clarity, not cruelty. A real cost to leaving.

Spinks did not invent this. He named it.

Manizales did not need a framework to work. But the framework helped me understand why it does.

Of course, there is an absurdity in comparing a city bound together by shared spiritual beliefs to modern communities organized around entertainment, hobbies, or fandom. A parish is not a bowling league. A faith tradition is not a Discord server. The stakes are different. The depth is different. The cost of leaving is different. But the underlying mechanics are not. In both cases, communities only endure when people feel responsible to something larger than themselves and to each other.

Losing our home taught me many things. But the deepest lesson did not come from loss. It came from landing somewhere that knew how to hold people when things fall apart.

Manizales did not save us. It absorbed us.

Legacy media talks about community endlessly, but confuses attention for belonging. What Manizales made clear is that real communities are slow, values-based, specific, and durable.

Belonging is not a tactic. It is a belief system.

The fires took our house. But they dropped us into a living example of what holds when everything else burns.

As our lives pull us back to the US, I will be forever grateful to this place. It brought us in and took care of us. We are part of its community. And I feel, without ever being forced to, a profound need to give back.

Wonderful piece and spot on. We all need more giving and less taking, as your experience shows. Thank you, Ben.

Thank you for sharing.