Sundance and the creator economy come from the same place, even if some people still resist the idea.

I once suggested in a Garden Stack about film schools that they should require students to open a YouTube channel. That suggestion triggered immediate pearl clutching in parts of the indie film community, including a film school head who seemed genuinely offended by the notion.

And yet, some of the most interesting and formally inventive work I encounter today is being born on YouTube. Work made outside traditional systems. Work that finds its audience before it finds permission.

There remains a reflexive discomfort in parts of the film world with the idea that independent art can live on the internet. A filmmaker with a YouTube channel. A series financed outside traditional lanes. For some, that still reads as dilution rather than continuation.

That reaction misses the point.

Independent filmmaking has always been about working outside the system to make work that does not fit neatly inside it. It has always been about reaching specific audiences instead of everyone at once, and about using whatever tools are available to get the work made and seen. The internet did not break that ethos. It amplified it.

I have been to Sundance twice with films that, without the festival’s spotlight and the awards they received there, would not have found distribution or meaningful exposure. Sundance mattered.

But if I were a young filmmaker starting today, I would be looking first to the power of the internet, not as a fallback, but as a primary path. Increasingly, Sundance itself seems aware of this tension.

The more Sundance recognizes this and invites real convergence with the internet, the more it is not reinventing itself, but returning to its roots.

Apologies we are a day late! Open Gardener Mitch Camarda was on the ground at Sundance, observing this convergence, and its limits, in real time. Below are those observations.

Notes From Sundance

Sundance was created to give independent storytellers a place to be seen, to offer new voices a platform outside the studio system and a chance to connect with niche audiences rather than chase mass appeal. From the beginning, the festival’s purpose was to elevate work that did not fit neatly inside existing commercial lanes and to protect the space where experimentation and specificity could survive.

Creators were never part of that original foundation, and that distinction matters. The filmmakers Sundance championed in its early years were operating outside dominant systems in ways that closely resemble how creators operate today, using whatever tools were available to make work, find audiences, and build momentum without waiting for permission. The tools have changed, but the impulse has not.

This year, it became clear that while the creator economy is present at Sundance, it is still not foundational to how the festival understands itself. Creators are visible, invited, and increasingly relied upon for reach and cultural relevance, but they remain largely external to the festival’s creative core, even as the need for that convergence has grown.

2026 marks the final year of the Sundance Film Festival in Park City before the festival relocates to Boulder, Colorado in 2027. Park City has never just been a backdrop, but part of the mythology shaped by isolation, friction, and the feeling that you had to really want to be there.

I went to Park City to understand what the festival feels like right now, at a moment when the industry it helped build seems to be pulling itself in different directions. With the passing of Robert Redford in 2025, the timing carried additional weight, as the institution he helped shape moves into a new chapter whether it wants to or not.

Arrival

The first thing I did when I arrived was go see a movie.

I had tickets for the late night screening of The Disciple, directed by Joanna Natasegara, at the Eccles Theatre. The film follows Cilvaringz, who was in the Wu-Tang Clan’s extended orbit, as he becomes increasingly consumed with the idea of making something singular during the period that led to Once Upon a Time in Shaolin, the single-copy album designed to reject the idea of music as disposable content and to argue for art as something scarce, intentional, and valuable.

As the film unfolds, it becomes clear that this is not a story about access so much as escalation. Cilvaringz is not trying to enter the room; he is trying to convince the room that protecting value matters more than reach. His fixation on creating something that resists mass distribution, even at the cost of misunderstanding or alienation, feels uncomfortably close to the position independent filmmakers occupy now. The film is less about Wu-Tang itself than it is about what happens when artists, already inside a system, attempt to push back against the incentives that system rewards.

The following thought came to mind: Creators aren’t replacing independent filmmakers. They’re becoming what independent filmmakers used to be.

That tension stayed with me throughout the rest of the festival.

Moving through Main Street made the scale of Sundance immediately apparent. Lines wrapped around brand houses and alumni cafés, and without a badge I hustled tickets through Reddit and a WhatsApp group run by Sean Glass of Reunion, which has become an informal but essential layer of festival infrastructure. Demand far outpaced access, and even ticket holders were often unsure whether they would get into screenings.

The mood, however, was not hostile. The phrase I heard most often was that people could not believe the festival was moving. With Robert Redford’s passing, the idea that Sundance was leaving Park City carried emotional weight, and many people had returned knowing this was a final chapter in a place that defined their relationship to independent film.

Filmstack, Saturday Morning

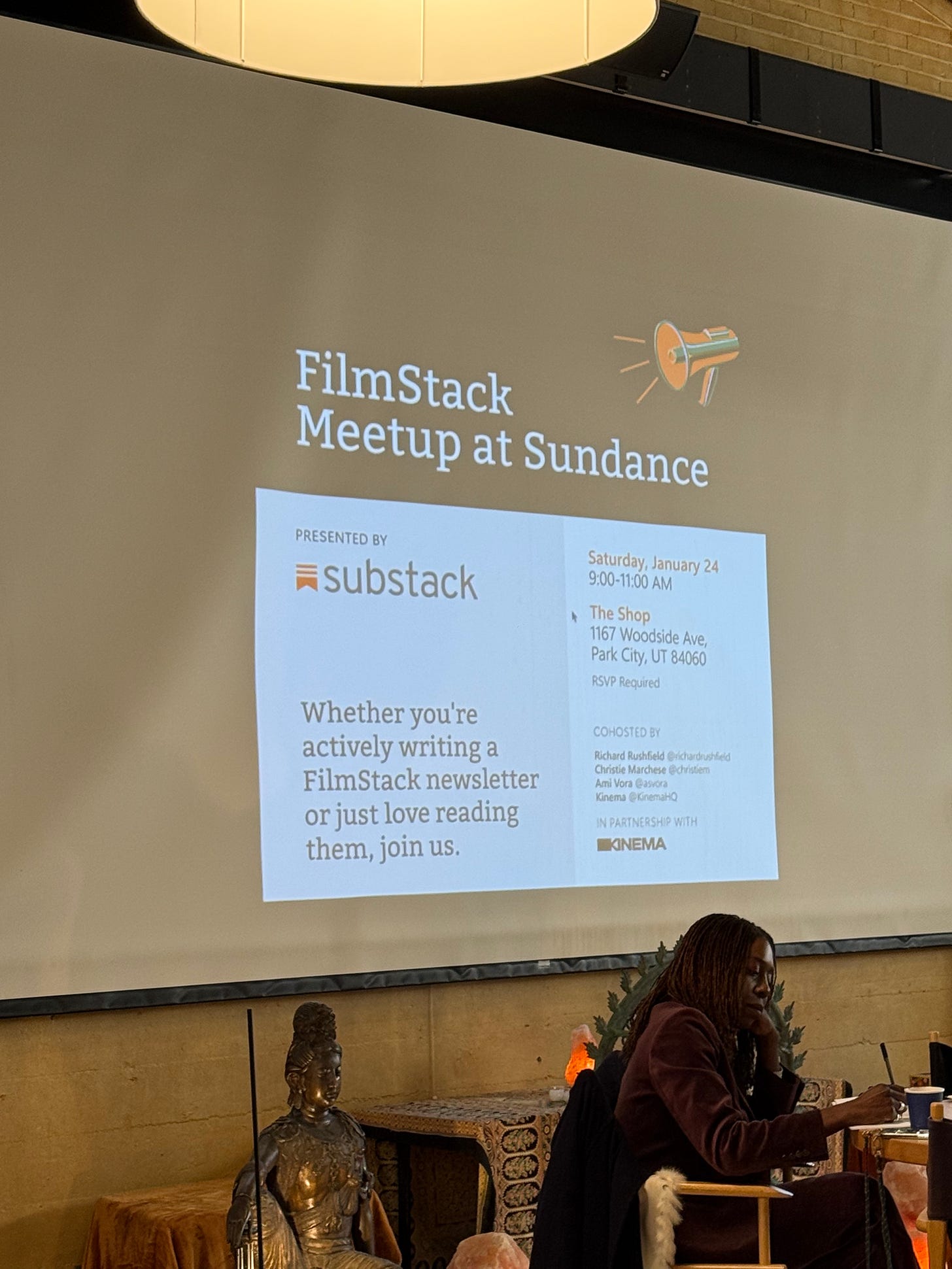

Saturday morning, Filmstack gathered at the Yoga Studio. The room held filmstackers, writers, educators, and students, including Ami Vora, Sam Widdoes, Dan Mirvish, and Susan Brewer Busa from Texas State, whose class I had spoken to the previous year about alternative pathways into a modern film career.

What connected the room was not job title but shared concern and curiosity about where independent film goes next. The conversation was open and informal, built entirely around people talking to one another rather than presenting ideas at one another. There were no laptops open and very few phones out, as the focus stayed squarely on face-to-face exchange.

Richard Rushfield spoke briefly to acknowledge the gathering and the importance of keeping this community connected, but the real substance lived in the conversations that followed. What stood out was the way the room functioned as a shared space for exploration, as people who think seriously about independent film found community with one another while informally circling how the pursuit continues to move forward.

The filmstack meetup mattered because it revealed something structural. These were some of the most urgent conversations about independent film happening all weekend, and they were happening outside Sundance’s official programming, even though they were deeply aligned with its original mission.

BrandStorytelling

BrandStorytelling is a Sundance-adjacent event focused on brand-funded films, documentaries, and series, positioning brand financing as a legitimate production model rather than a compromise.

I did not go there to attend the event itself, but to meet a friend who is a social-native filmmaker working in microdramas. We had crossed paths digitally many times but had never met in person, and BrandStorytelling happened to be where they were based that afternoon.

The contrast with Main Street was immediate. The space was quiet and unhurried, and the conversations felt removed from the scramble for access downtown. From what I could see, the focus remained on brand-backed projects supported by companies like Yogi Tea, Lenovo, Intel, Sephora, and Accenture, and on treating brand funding as a viable and scalable way to get work made.

Our conversation centered on microdrama as an emerging form, on story structure in vertical formats, and on how financing models shape creative risk. We talked about when the first million-dollar microdrama might arrive, or when an A-list actor might participate not as a novelty, but as a serious creative experiment. What stood out was how open the exchange felt, especially compared to similar discussions I had attempted in more traditional film contexts prior to Sundance, which often stalled or turned defensive.

BrandStorytelling did not feel oppositional to Sundance, but it did feel like parallel infrastructure, operating quietly alongside a festival still oriented around legacy financing paths.

Creators at Sundance

Creators were present at Sundance this year, but they were not foundational to the festival’s structure.

What made that absence more noticeable was the contrast with last year. In 2025, Sundance made a more explicit effort to integrate creators through an invite-only Creator Day. That event was Sundance-sanctioned and brought leading creators into direct conversation with industry, brands, and filmmakers, not simply as marketing partners but as cultural operators in their own right.

Participants included creators such as Sean Evans, Rhett McLaughlin, Link Neal, Michelle Khare, and Kinigra Deon. The presence of creators like Deon, whose work is built entirely through direct audience relationships outside traditional Hollywood systems, made the intent of the event clear. Sundance was acknowledging that creators were not adjacent to independent storytelling, but part of its present and future.

This year, that layer was noticeably absent.

Creators were still present, but primarily through marketing, amplification, and adjacent programming. TikTok made their presence known by inviting film-focused creators to Park City, including Louis Levanti and Kit Lazer, embedding creators into the festival’s outward-facing ecosystem through coverage, interviews, and red-carpet content. Sundance’s marketing reflected that shift, with Charli XCX becoming one of the festival’s most visible cultural figures through her appearances in multiple films.

Creator-adjacent conversations also appeared at the Impact Lounge, Sundance’s hub for social impact and narrative change, where digital-native voices were framed around audience reach and cultural influence rather than as part of the festival’s creative core.

Creator-informed infrastructure showed up more quietly in the lineup through If I Go Will They Miss Me, directed by Walter Thompson-Hernández and produced by Further Adventures. Further Adventures, founded by YouTube veteran Steven Beckman and producer Ben Stillman, works with independent filmmakers and creators to develop and produce projects, applying creator-era audience strategy to long-form storytelling. Further Adventures have a second film in the festival, from filmmaker Ramzi Bashour, titled Hot Water. Like Thompson-Hernández, Bashour’s previous short demonstrated his ability to connect with audiences.

Beckman’s background in representing creators at YouTube informs that approach. The company’s goal, in addition to helping creators elevate their storytelling and transition into film, is also to apply lessons from creator-native ecosystems, such as direct audience relationships and sustainable creative businesses, to support filmmakers with singular voices. Thompson-Hernández’s film embodies that model, expanding on his Sundance-winning short from 2022 while retaining its intimacy and specificity.

The clearest convergence moment for me came in the midnight shorts block, when Homemade Gatorade, an animated short by Carter Amelia Davis, played to one of the strongest audience reactions of the weekend. Davis already had an active Patreon community and an online audience before Sundance programmed the film, underscoring that the festival is already selecting work shaped by direct audience relationships, even if it does not yet talk about it that way.

Taken together, these moments suggest that creators are present, visible, and increasingly important to Sundance’s ecosystem, but they are still not embedded as a central organizing principle.

Leaving Park City

Getting to Sundance has always been the dream, both for me and for nearly every filmmaker I spoke to during my short time there, and it remains my dream to have a piece of work play at the festival, no matter where it is held.

Sundance understands that it needs creator-native voices to help extend its community and reach, and that process is already underway through partnerships and marketing. The deeper opportunity, however, feels structural, not simply using creators to push the festival outward, but inviting creators who already have communities into the creative fabric of the festival itself.

Boulder represents a real opportunity in that regard. Unlike Park City, it is a college town with tens of thousands of students and emerging artists living there year-round. That environment has the potential to reconnect Sundance with the kinds of new voices and niche audiences it was originally built to serve.

The ethos that made Sundance essential does not belong to a town. It belongs to the belief that new voices are worth the effort it takes to hear them.

It is simply waiting to be made foundational again.

Great article as always and agree. Minor correction but significant, I think- the Creator day was curated by and run by BrandStorytelling as well, not Sundance. And the Impact lounge is an independently curated event.

Both are official partners to not go rogue, and I’m on the advisory board of BST so biased, but it shows the Creator inclusion was on the margins and still less officially affiliated.